Nicole Farhi

For any information on this exhibition or the availability of the works please do

email us at the gallery: info@beauxartslondon.uk or telephone us: 07917 405 747

For any information on this exhibition or the availability of the works please do

email us at the gallery: info@beauxartslondon.uk or telephone us: 07917 405 747

Please Click Link Above

PRESS RELEASE – Folds by Nicole Farhi

Please Click Link Above

Harper’s Bazaar (UK) March Issue 2019

Please Click Link above

Please Click Link above

Please Click Link above

Please Click Link above

Please Click Link above

Independent.co.uk (UK) 20th December 2018

Please Click Link above

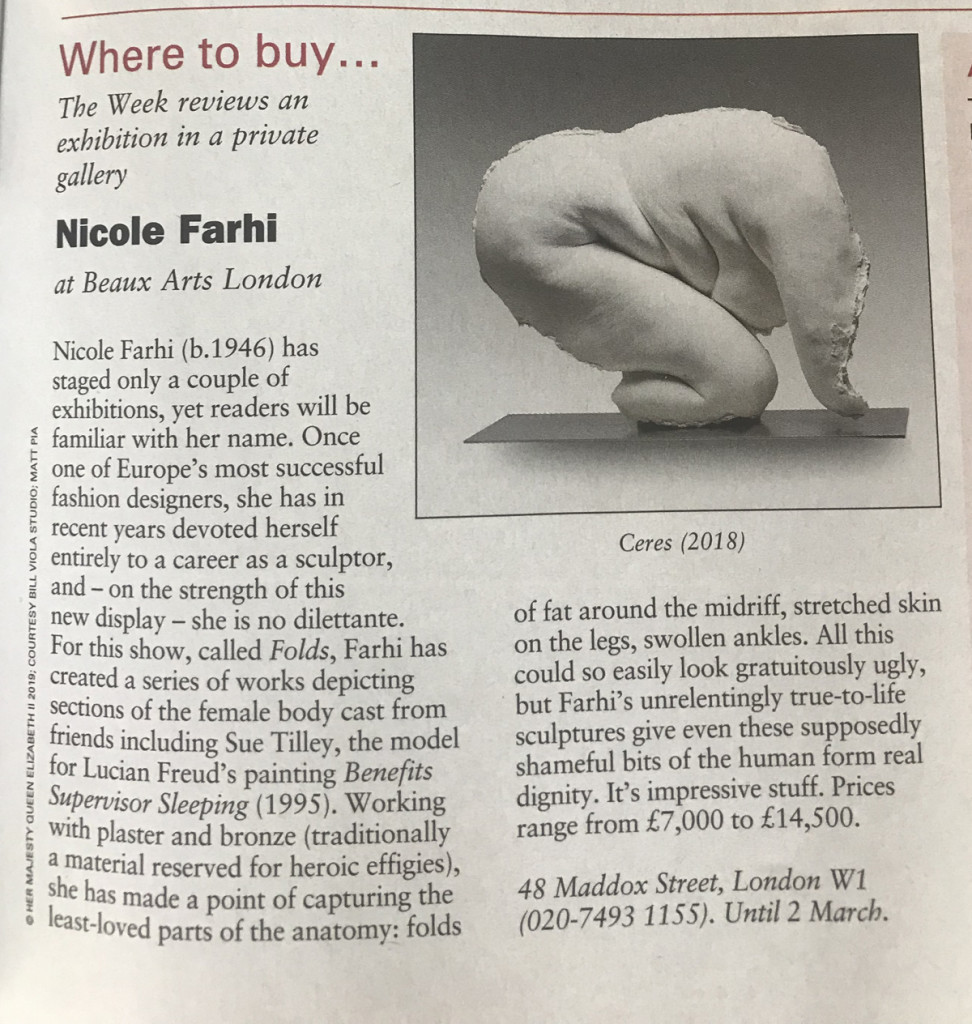

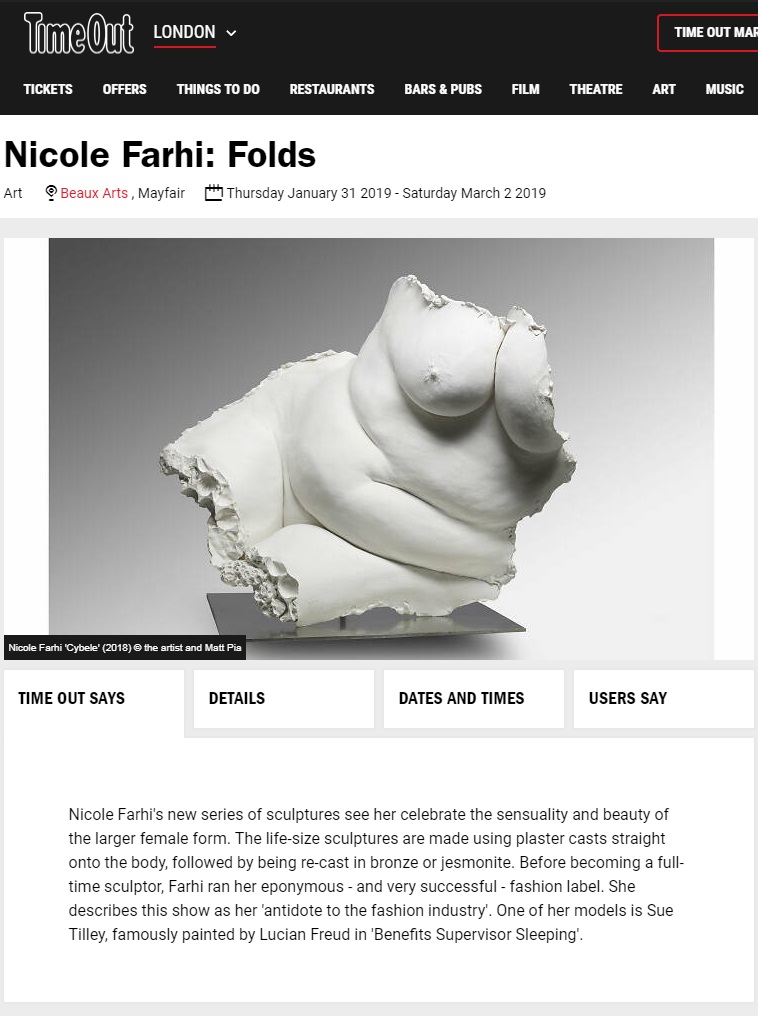

Nicole Farhi Folds It all starts with Auguste Rodin. On a visit to London in 1903, he found himself overwhelmed by the battered yet heroic beauty of the ancient Greek Elgin Marbles in the British Museum. This encounter caused him to change the way he treated the naked body in his sculptures. He decided to introduce the fragment, omitting heads and limbs, believing that a torso was equally as expressive as a full body, and sometimes more so. The poet and secretary to Rodin, Rainer Maria Rilke, wrote of these works : ‘Each of these fragments is of such a peculiarly striking unity, so possible by itself, so little in need of completion, that you forget they are only parts.’ The same can be said of Nicole Farhi’s new body of work, Folds. Her previous series, also comprising isolated body parts, saw Farhi producing a fascinating inventory of the gestures of the human hand. And even while she was working on Hands, the new series was forming in her mind. ‘Following my last exhibition … I wanted to continue looking at parts of the human body; this time exploring the powerful beauty of flesh, curves, and the sexual energy large women have.’ Two well-endowed female friends were content to let Farhi loose on their bodies, while she swiftly smoothed wet alginate onto their skin, and positioned swathes of bubble wrap to create an edge to hold the alginate in place. Then she covered the set but flexible alginate with strips of plaster bandages to reinforce the cast before it is lifted off the body, a risky manoeuvre. The negative part of the cast is then filled with plaster and left to cure for a day or two before Farhi can see what the positive cast of the body fragment looks like. Decisions about the size and shape of the work had to be made well in advance of this hectic activity. Farhi set the model in a pose that she was comfortable holding and took a photograph. Drawing lines on this photograph allowed her to settle on the area to be cast, so both sculptor and model knew what was to occur. Instead of creating a sharp cut edge to the cast, Farhi let the dimpled bubblewrap show its lively texture, nestled against the more subtle silky finish of human skin. This adds a little touch of expressive drama to the contour. The first work she made using this method, Breast/Gaia, is the most arresting of all the Folds in its simplicity and potency. Comprising a single weighty breast set atop a gently curved fleshy support, it stands erect, not unlike a totemic female icon from Neolithic times. A major proportion of the earliest works of world sculpture are goddess figures, and these powerful matriarchal women have left a subtle but indelible imprint on the Western psyche. As the Folds series grew, Farhi realised that she was making works that called back to those early times: ‘Each fragment is named after a Greek or Roman goddess. Something in my work reminded me of the beginning of humanity. I looked into Greek mythology and found the similarities between those sensual powerful deities and my earthly goddesses.’ Gaia was known in ancient Greek times as the primal mother goddess of all human life, described by the Greek poet Hesiod as ‘wide-bosomed’. Another primal goddesses was Demeter, and Farhi has given her a more upright, less folded, pose, presenting the twist of her back and her shoulder. Demeter was a strong willed goddess, arguing with Zeus, and Farhi’s fragment is an evocation of that energy and resolve. Many of the other fragments, such as Ceres, Hebe, Cybele, and Hypnos are richly enfolded upon themselves, allowing at least two major folds or creases to appear between shoulder and thigh. There are two casts which focus on the legs alone. Repose has a neatly bent, shapely leg with the heel tucked into the buttock, while Rising consists of two legs, and for me brings to mind a hen bird sitting on her eggs keeping them safe before incubation. However Farhi has titled this work Rising, and the title suggests a latent energy. The most minimal piece is that of Juno, Roman goddess of the gods. In her role as queen she kept special watch over all aspects of women’s lives, and was known as the protector of women in confinement. Farhi presents her lying peacefully on her side, as though empathising with the pregnant women she oversees. Having lifted the alginate negative moulds from her model’s bodies, Farhi then had two choices to make; what material should they be cast in, and what colour. She likes white Jesmonite , a type of reinforced plaster, for its capacity to pick up the delicate textures of skin, so the Folds are cast in that material, lending them an aura of purity and quietness. Farhi has also had four of them cast in bronze, which has been treated to a matt black graphite patina. By changing the casting medium and hue, she wanted to show that the sculptures take on a different meaning, with the black casts becoming more dramatic. Looking at the group of Folds in Farhi’s studio, I felt that I had been granted special access to a women-only space, to a harem of serene creatures, content to be together in all their nakedness. In 1904 Matisse painted a work which he titled Luxe, calme et volupte, a line taken from the poem L’invitation au voyage by the French poet Charles Baudelaire. The poem was about an escape to an imaginary tranquil refuge, exactly what Farhi has conjured up for our pleasure; a new series of sculptures infused with luxe, calme et volupte. Judith Collins Author and Former Senior Curator, Tate