1930 Born November 14 in Thurlow, Suffolk

1941-47 Attends Convent of the Holy Family, Exmouth Studies at Guildford School of Art

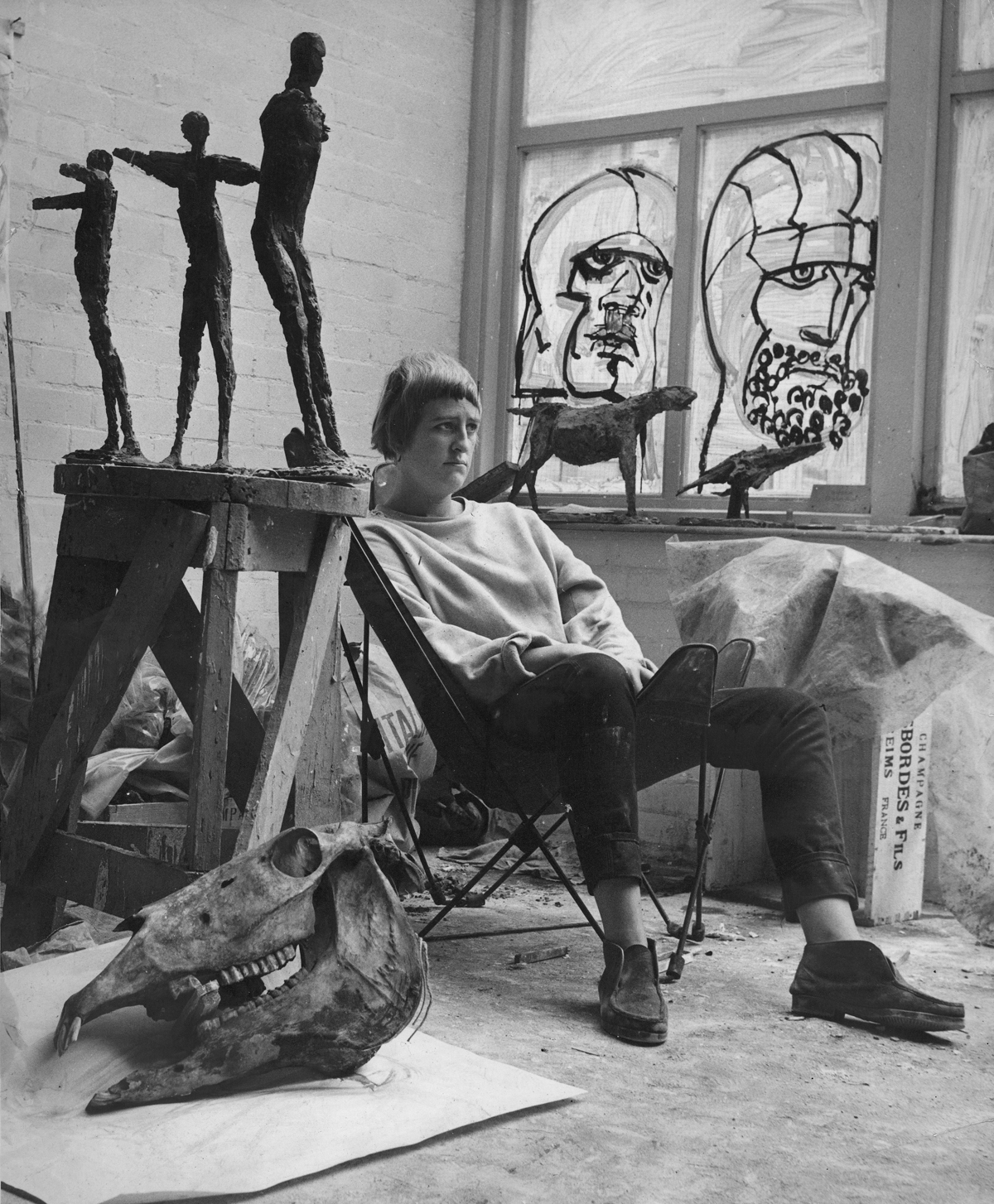

1949-53 Studies at Chelsea School of Art under Bernard Meadows and Willi Soukop

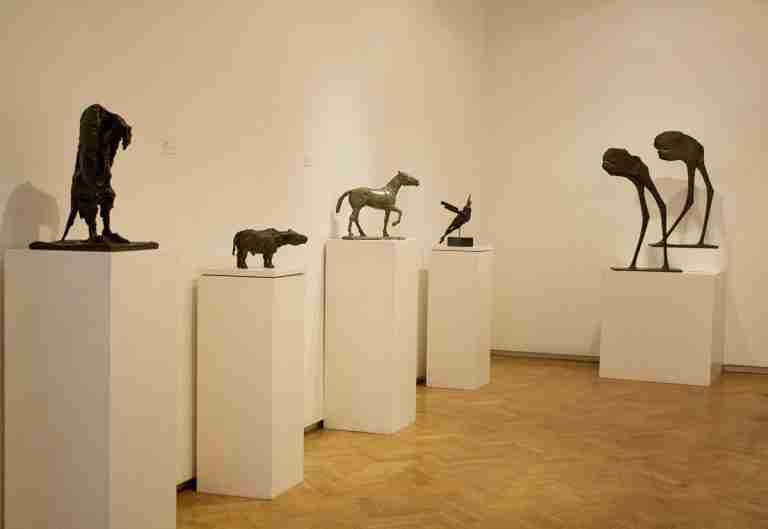

Exhibits with London Group Tate Gallery purchases Bird

1953-61 Teaches at Chelsea School of Art

1953 Wins prize in competition for Monument to the unknown political prisoner Arts Council purchases Bird

1954-62 Teaches at St Martin’s School of Art, London

1955 First solo exhibition at St George’s Gallery, London Marries Michel Jammet

1957 First major public commission from Harlow New town (Boar)

Commission for Bethnal Green housing scheme, Blind beggar and dog

Contemporary Arts Society purchases Wild Boar Joins Waddington Galleries

Commission for London County Council (Birdman) Birth of her son Lin Jammet

1960 Commission for façade of Carlton Tower, London Felton Bequest purchases Birdman (National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne)

Commission for Coventry Cathedral (Eagle lectern)

Commission for Manchester Airport (Alcock and Brown memorial)

Commission for Ulster Bank, Belfast, Flying figures Divorces Michel Jammet Eagle installed as J F Kennedy memorial, Dallas, Texas

Commission for Our Lady of the Wayside, Solihull (Risen Christ) Marries Edward Pool

1965-67 Visiting Instructor, Royal College of Art, London

1966 Commission for Liverpool Cathedral (Alter cross)

Moves to France Illustrates Aesop’s Fables, published by Alistair McAlpine and Leslie Waddington Awarded CBE

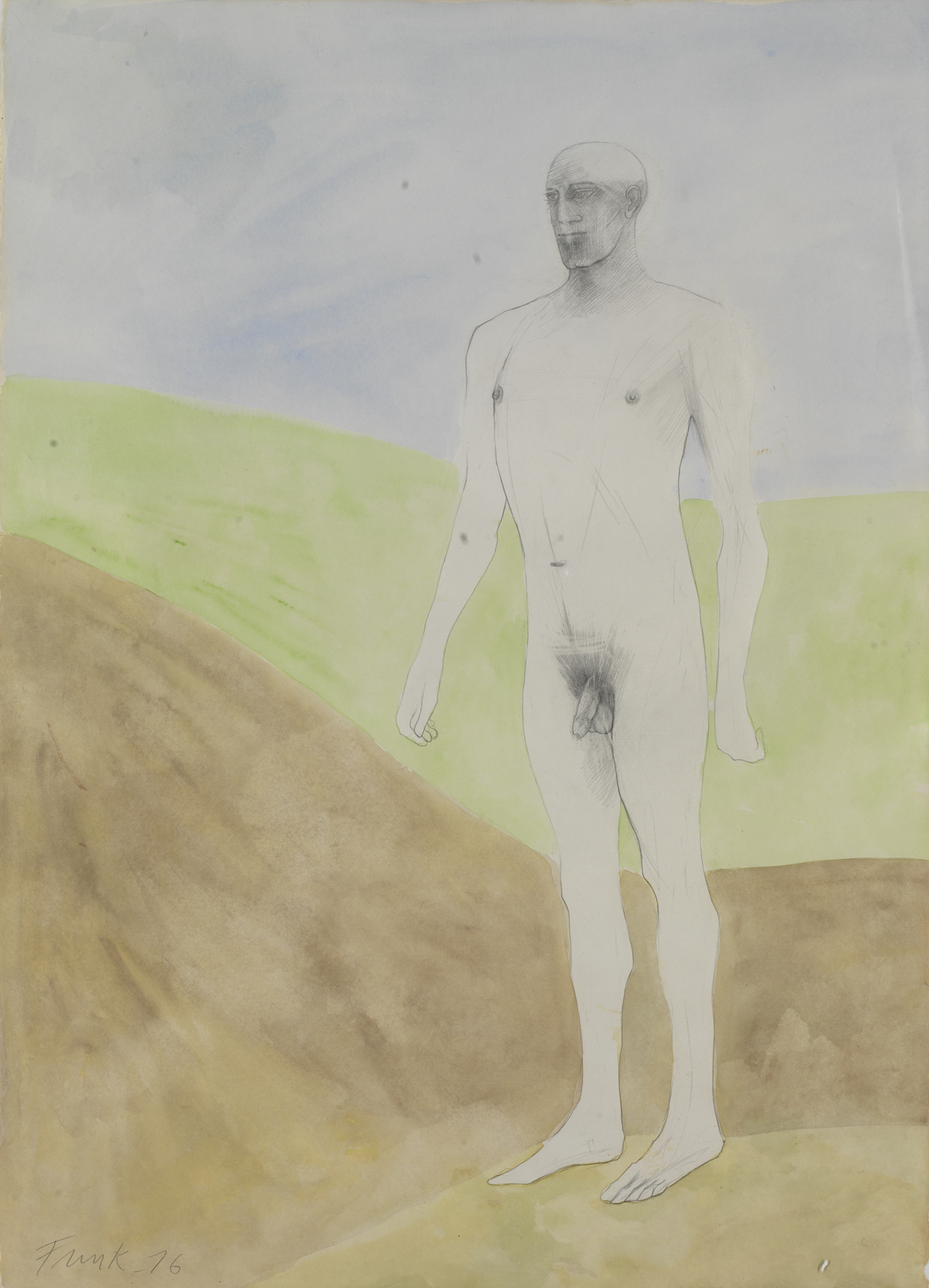

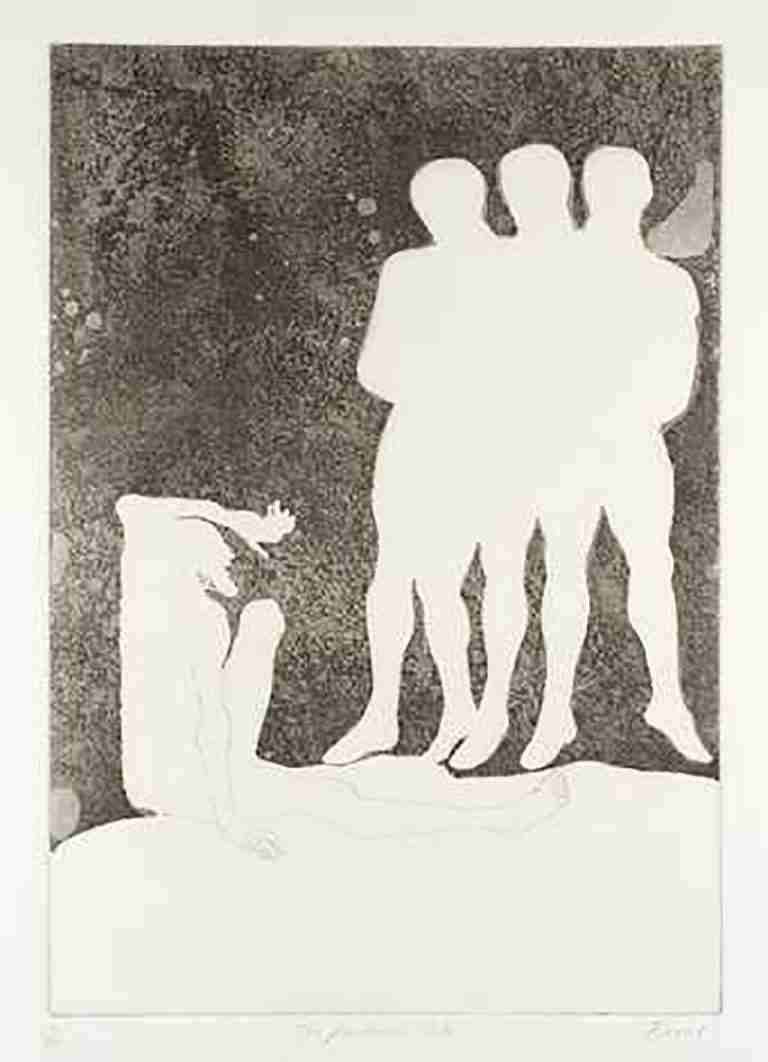

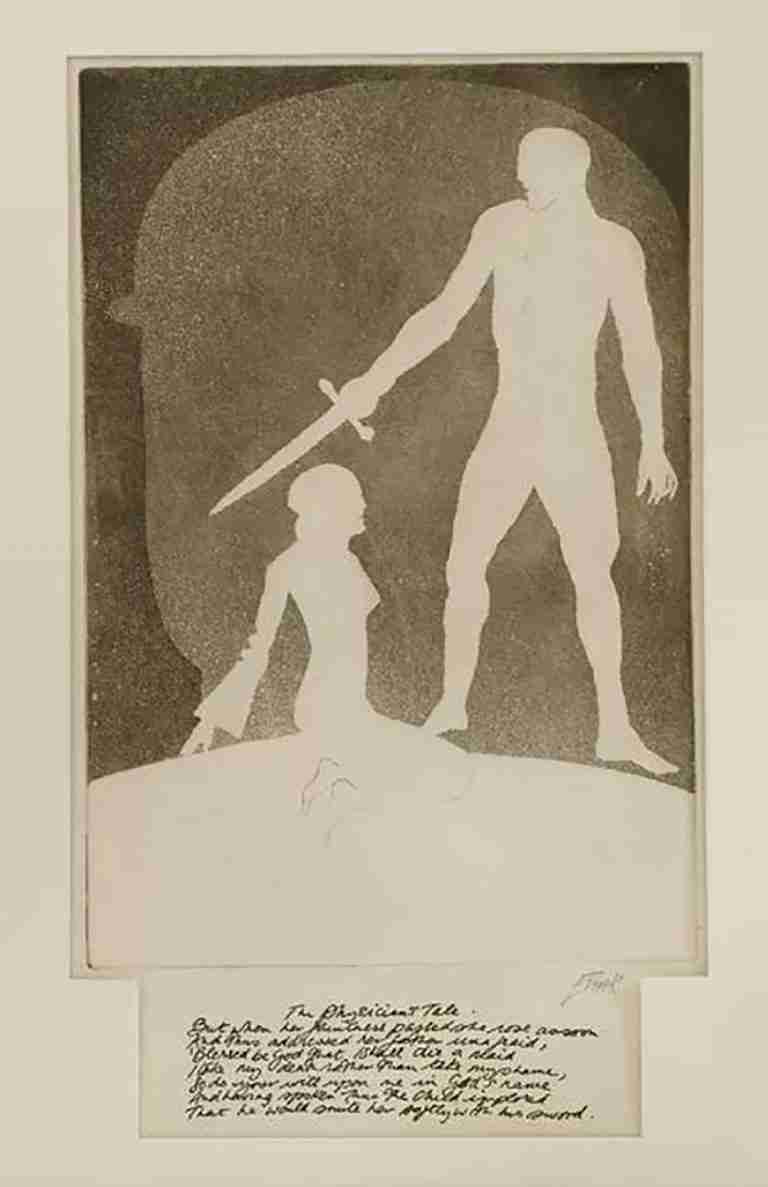

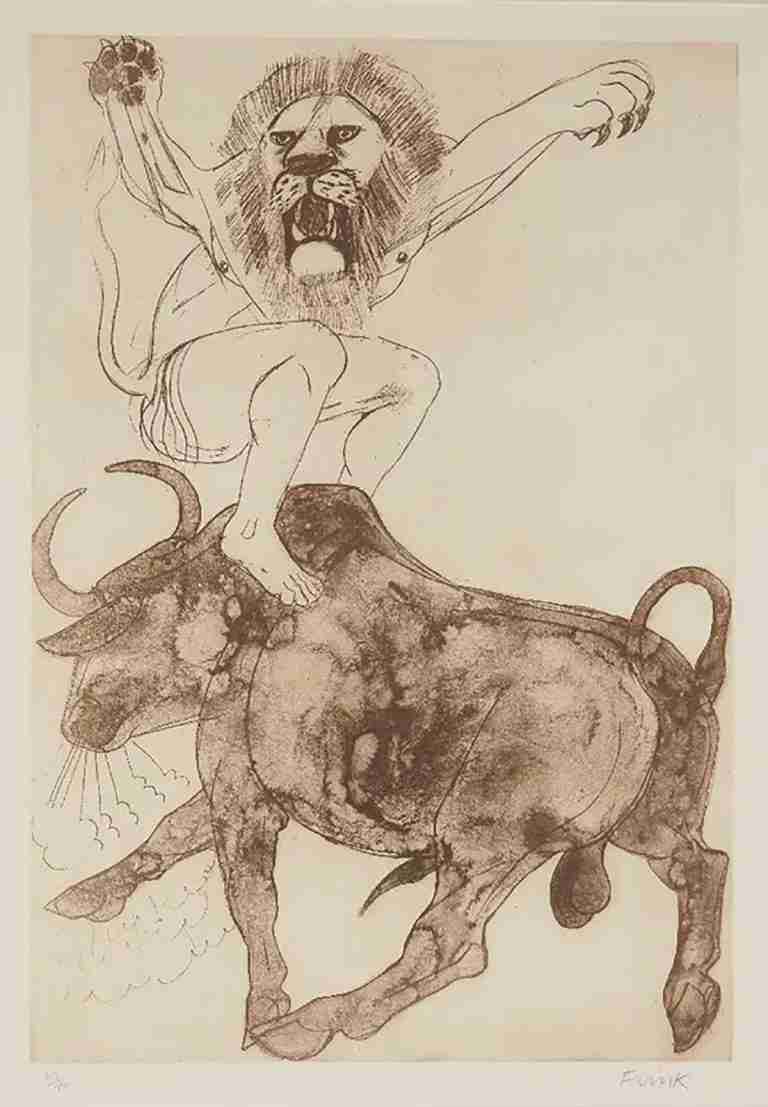

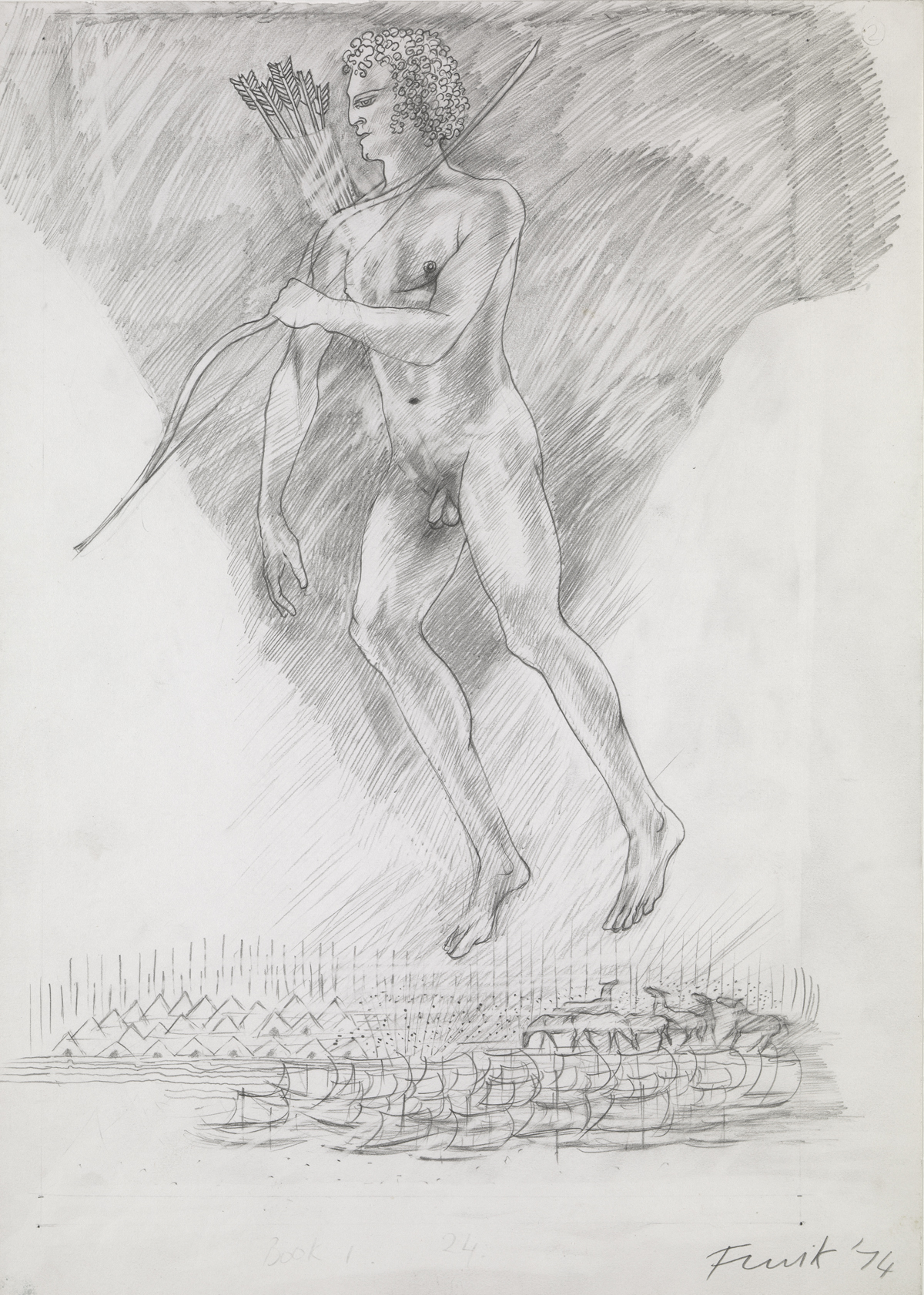

1971 Elected Associate of the Royal Academy of Arts First shows in Royal Academy Summer Exhibition Illustrats Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, published by Leslie Waddington Separates from Edward Pool and returns to England Illustrates Homer’s Odyssey, published by The Folio Society

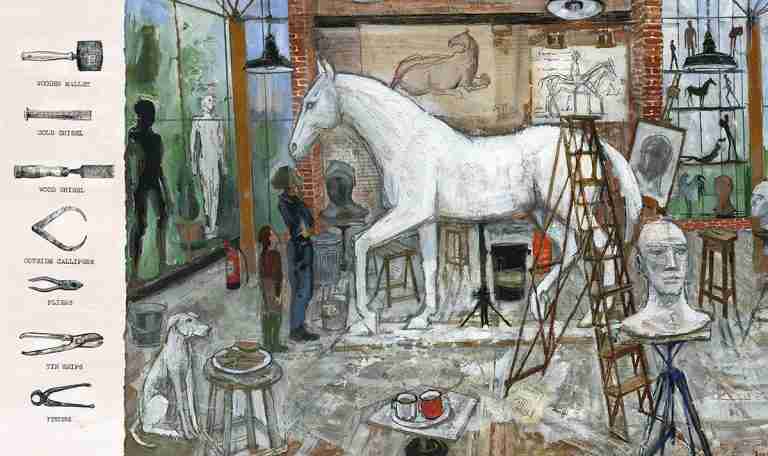

Commission for de Beers, trophy for King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes Com mission for Dover Street, London (Horse and Rider)

Marries Alexander Csáky

1975 Commission for Paternoster Square, London (Paternoster)

Illustrates Homer’s Illiad, published by The Folio Society Elected to board of trustees, British Museum

1976 Appointment to the Royal Fine Art commission

Moves to Dorset Elected Royal Academician Awarded Honorary Doctorate by University of Surrey

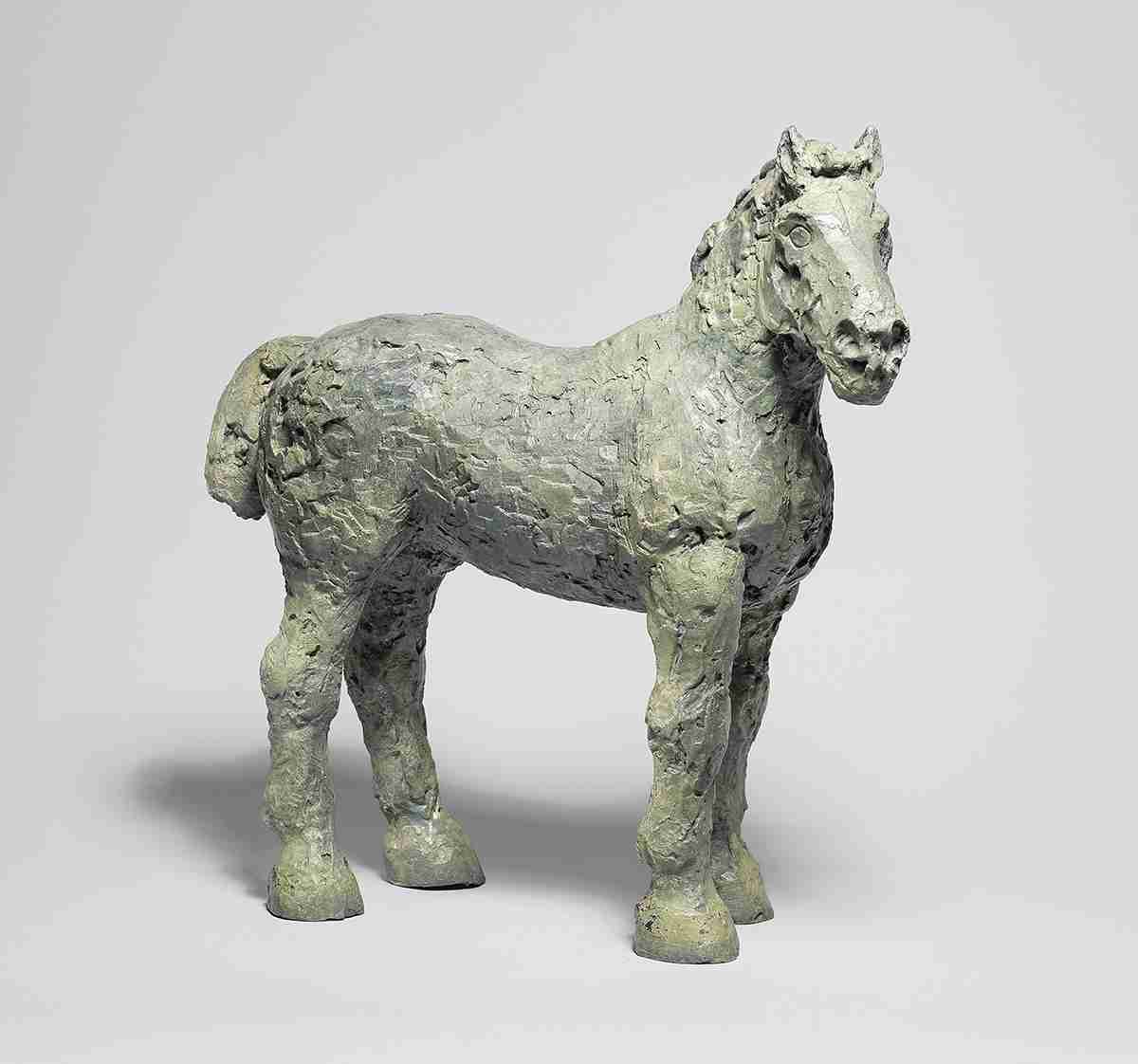

Commission for Milton Keynes (Horse)

1980 Commission for Goodwood Racecourse (Horse) Appointed Trustee, Welsh Sculpture Trust

Awarded DBE Com mission for Brixton Estates, Dunstables (Flying Men)

Awarded Doctorate by Royal College of Art

Commission for All Saints Church, Basingstoke (Christ)

Illustrates Kenneth McLeish’s Children of the Gods, published by Longman

Awarded Honorary Doctorate by Open University

Awarded Doctorate of Literature by University of Warwick

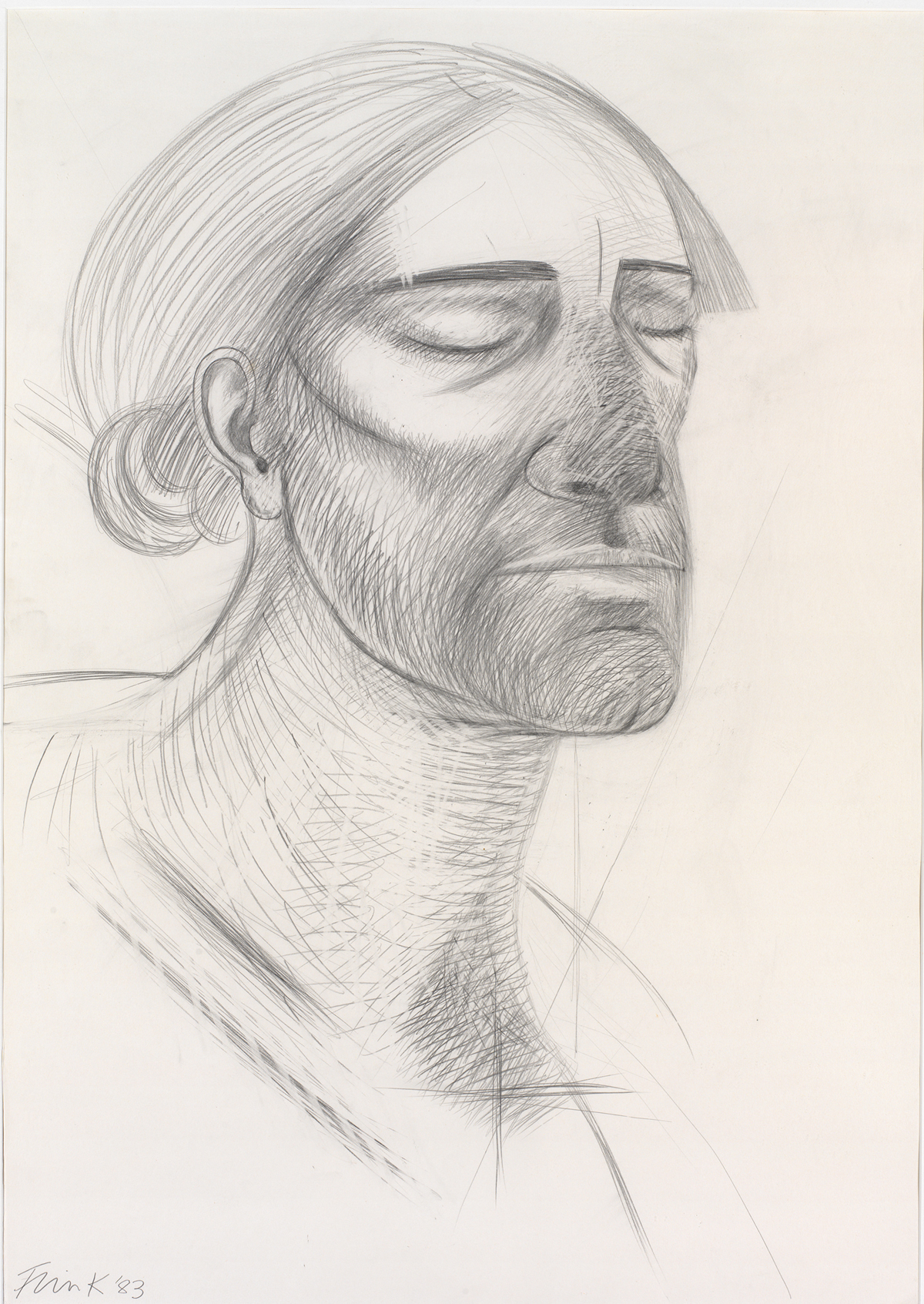

1984 Solo Exhibitions: St Margaret’s Church, King’s Lynn, Norfolk; University of Surrey, Guildford Group Exhibitions: British Artists’ Books 1970-1983, Atlantis Gallery, London; Drawings, School of Art, Guildford, Surrey; Man and Horse, Metropolitan Museum, New York

1985 Solo Exhibitions: Royal Academy of Arts, London; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge; Waddington Graphics, London

1986 Solo Exhibitions: Beaux Arts, Bath; Poole Arts Centre, Poole, Dorset; David Jones Art Gallery, Sydney; Read Stremmel, San Antonio, Texas Group Exhibitions: Menagerie, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Bretton Hall, Wakefield; Barbican Centre, London; Chicago Art Fair

1987 Solo Exhibitions: Beaux Arts, Bath; Coventry Cathedral, Warwickshire; Chesil Gallery, Portland, Dorset (graphics); Arun Art Centre, Arundel, Sussex; Bohun Gallery, Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire Group Exhibitions: Abbot Hall, Cumbria; Royal College of Art, London; Albemarle Gallery, London; Kingfisher Gallery, Edinburgh; Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy, London; Salisbury Ecclesiastical Festival, Wiltshire; Thomas Agnew, London; Self Portrait, Art Site, Bath, Avon (touring)

1988 Awards: Honorary Doctorate, University of Cambridge; Honorary Doctorate, University of Exeter Solo Exhibitions: Keele University, Staffordshire; Ayling Porteous Gallery, Chester, Cheshire (graphics)

Group Exhibitions: Expo ’88, Brisbane; Harris Museum and Art Gallery, Preston, Lancashire; Angela Flowers Gallery, London

1989 Awards: Honorary Doctorate, University of Oxford; Honorary Doctorate, University of Keele; Retires from the board of Trustees of the British Museum Solo Exhibitions; Hong Kong Festival; Fischer Fine Art, London; Lumley Cazalet, London (prints); New Grafton Gallery, London (drawings) Group Exhibitions: President’s Choice, Royal Academy and the Arts Club, London; Sacred in Art, Long and Ryle, London; The National Rose Society, Lincolnshire; Grape Lane Gallery, York; Tribute to Turner, Thomas Agnew, London

1990 Award: Honorary Doctorate, University of Manchester Solo Exhibitions: The National Museum for Woman in the Arts, Washington D.C.; Compass Gallery, Glasgow

1991 Award: Honorary Doctorate, University of Bristol Solo Exhibitions; Galerie Simonne Stern, New Orleans; Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York; Chesil Gallery, Portland, Dorset; Bohun Gallery, Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire Group Exhibition: Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy, London

1992 Award: Companion of Honour

1993 Dies 18 April

Exhibitions since 1993

Memorial Exhibition, Beaux Arts, London

Beaux Arts London, solo exhibitions: 1995, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2002, 2009, 2013, 2015, 2018, 2024

Elisabeth Frink, Memorial Exhibition, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Goodwood Sculpture Park, Chichester

1997 Salisbury Festival Exhibition (with the Edwin Young Trust, Salisbury and Dorset County Museum, Dorchester)

1997 Elisabeth Frink 1930-1993, Beaux Arts, London

1998 Kilkenny Festival Exhibition, Ireland

1998 Lumley Cazalet, London

Fifty Years of British Sculpture, Den Haag, Netherlands

Witley Court Sculpture Park Exhibition, Worcester

2000 Beaux Arts, London

2001 Elisabeth Frink, Djanogly Art Gallery, Nottingham University

2002 Beaux Arts, London Head On(Art with the brain in mind),

The Science Museum, London (Wellcome Trust)

Elisabeth Frink, Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Beaux Arts, London

2006 Beaux Arts, London

2009 Beaux Arts, London 2011 Elisabeth Frink, Beaux Arts London

2013 “Elisabeth Frink Catalogue Raisonné of Sculpture 1947-93”, published by Lund Humphries, to commemorate 20 years since her death Elisabeth Frink (catalogue), essay by Annette Ratuszniak, Beaux Arts, London

2015 Elisabeth Frink, Beaux Arts London

2015 – 2016 Elisabeth Frink: The Prescence of Sculpture, Djanogly Gallery Lakeside Arts, Nottingham

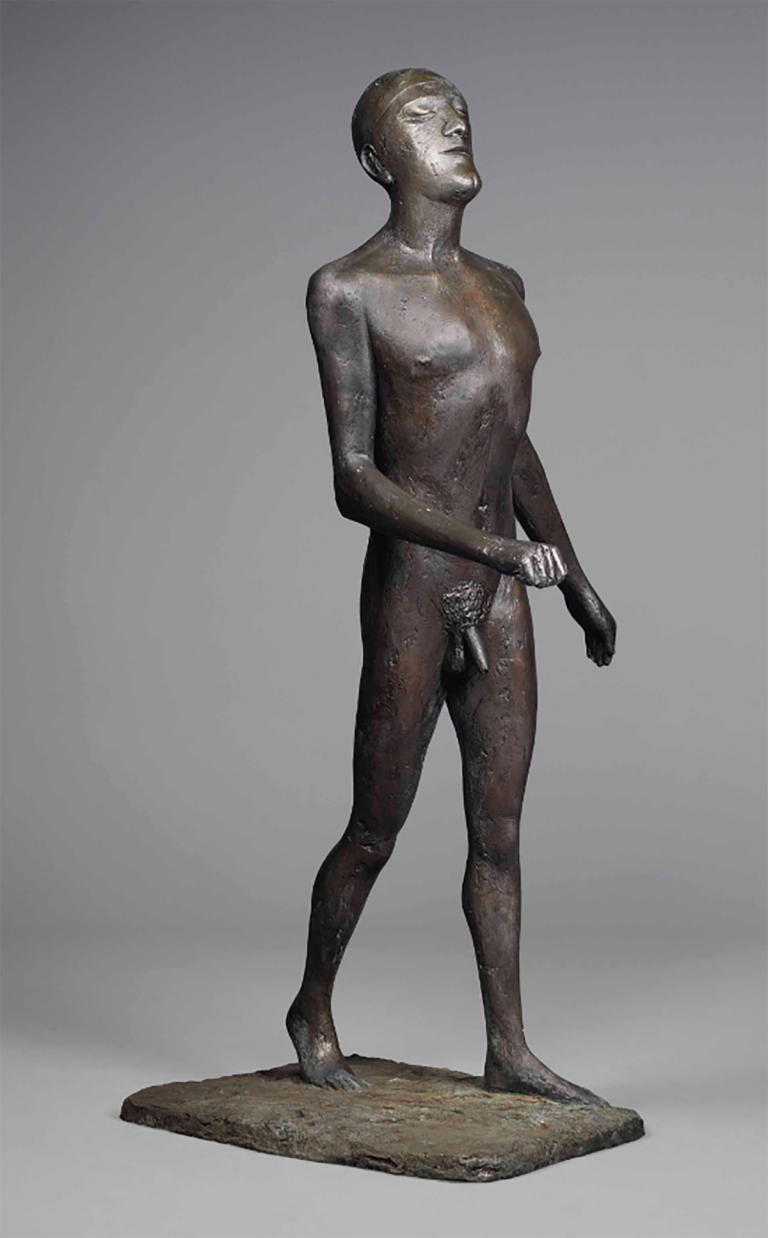

2017 Elisabeth Frink: Transformation, Hauser and Wirth, Bruton

2018 Elisabeth Frink, Beaux Arts London

2018- 19 Elisabeth Frink: Humans and other Animals Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University

of East Anglia, Norfolk

2021 Man is Animal Gerhard Marcks Haus, Bremen, Germany

2023 A View from Within, Dorset Museum and Art Gallery, Dorchester

2024 A Celebration, Beaux Arts, London

Publications

1968 Gray, R., Frink, Bratby, Barnes, Jackson, East Kent and Folkestone Arts Centre 1

972 Mullins, E., The Art of Elisabeth Frink, Lund Humphries, London

1984 Elisabeth Frink, Sculpture, Catalogue Raisone é , Harpvale Press, Wiltshire

1985 Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture and Drawings 1952-1984 (catalogue), curated by Sarah Kent, Royal Academy of Arts, London 1989 Cameron, N., and Frink, E., Elisabeth Frink: Recent Sculptures and Drawings (catalogue), Fischer Fine Art, London

1990 Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture and Drawings 1950-1990 (catalogue), The National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C. 1994 Elisabeth Frink (catalogue), introduction by Peter Murray; Yorkshire Sculpture Park, Wakefield

1994 Lucie-Smith, E., and Frink, E., Frink, a Portrait, Bloomsbury

1994 Sculpture and Drawings 1965-1993 (catalogue), preface by Edward Lucie-Smith, Lumley Cazalet, London 1994 Lucie-Smith, E., Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture since 1984 and Drawings, Art Books International

1997 Elisabeth Frink 1930-1993 (catalogue), foreword by Edward Lucie-Smith, Beaux Arts, London

1997 Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture and Drawings 1966-1993 (catalogue), Lumley Cazalet, London

1997 Elisabeth Frink – A certain unexpectedness – Sculpture, Graphics and Textiles (catalogue), foreword by Canon Jeremy Davies; ‘Elisabeth Frink’ by Edward Lucie-Smith, ‘A certain unexpectedness’ by Annette Downing; ‘Man and the Animal World’ by John Hubbard, Salisbury Festival with the Edwin Young Trust, Wiltshire County Council and Dorset County Museum Gardiner, S., Frink, The official biography of Elisabeth Frink, Harper Collins Wiseman, C., Original Prints, Catalogue Raisonné, Art Books International 2002 Elisabeth Frink, Sculptures and Drawings (catalogue), foreword by Edward Lucie-Smith, Beaux Arts, London

2004 Elisabeth Frink (catalogue), foreword by Elspeth Moncrieff, Beaux Arts, London

2006 Elisabeth Frink (catalogue), foreword by Brian Phelan, Beaux Arts, London

2009 Elisabeth Frink (catalogue), essay by Germaine Greer, Beaux Arts, London

2011 Elisabeth Frink (catalogue) essay by Julian Spalding, Beaux Arts London

2013 “Elisabeth Frink Catalogue Raisonné of Sculpture 1947-93”, published by Lund Humphries, to commemorate 20 years since her death Elisabeth Frink (catalogue), essay by Annette Ratuszniak, Beaux Arts, London

2015 Elisabeth Frink (catalogue), essay by Andrew Lambirth, Beaux Arts, London

2015 – 2016 Elisabeth Frink: The Prescence of Sculpture, Djanogly Gallery Lakeside Arts, Nottingham – Illustrated catalogue to to accompany by Annette Ratuszniak (Curator, Frink Estate) with Neil Walker (Head of Visual Arts Programming).

2018 Elisabeth Frink (catalogue) essay by Andrew Lambirth, Beaux Arts London

2018- 19 Elisabeth Frink: Humans and other Animals (catalogue) Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, Norfolk

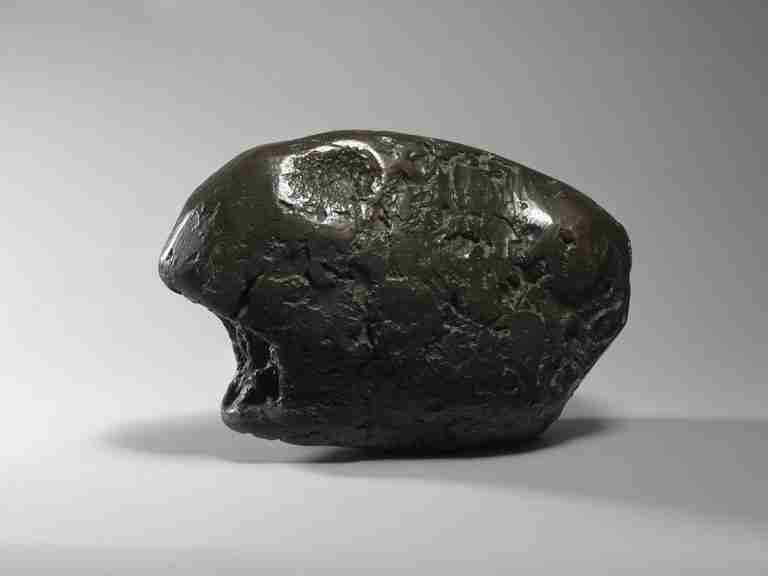

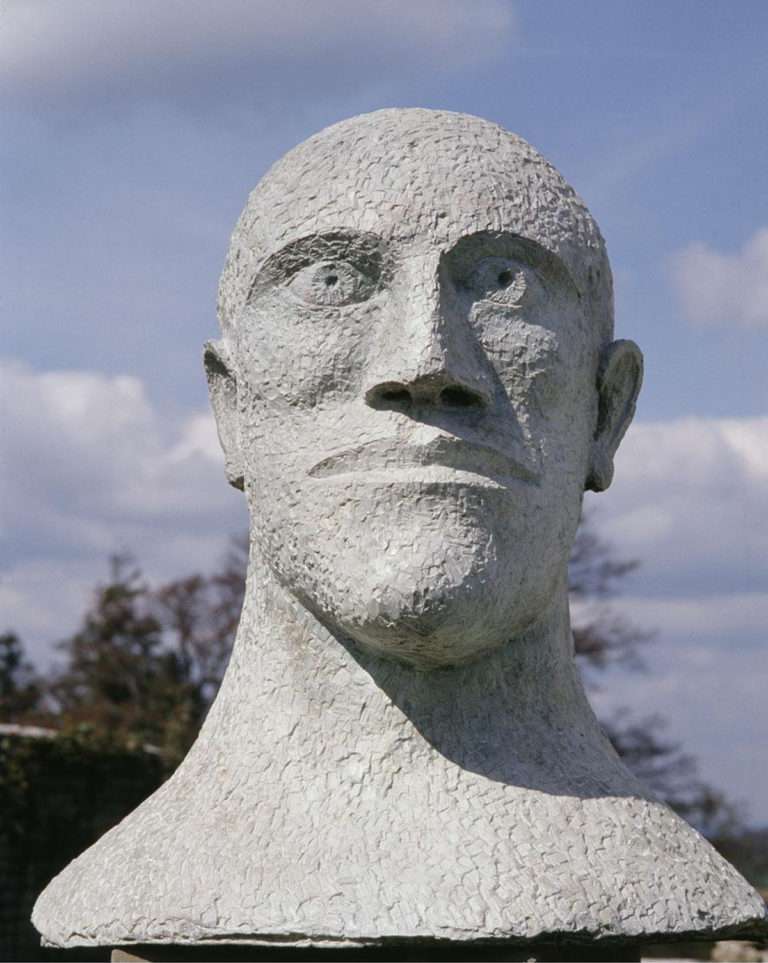

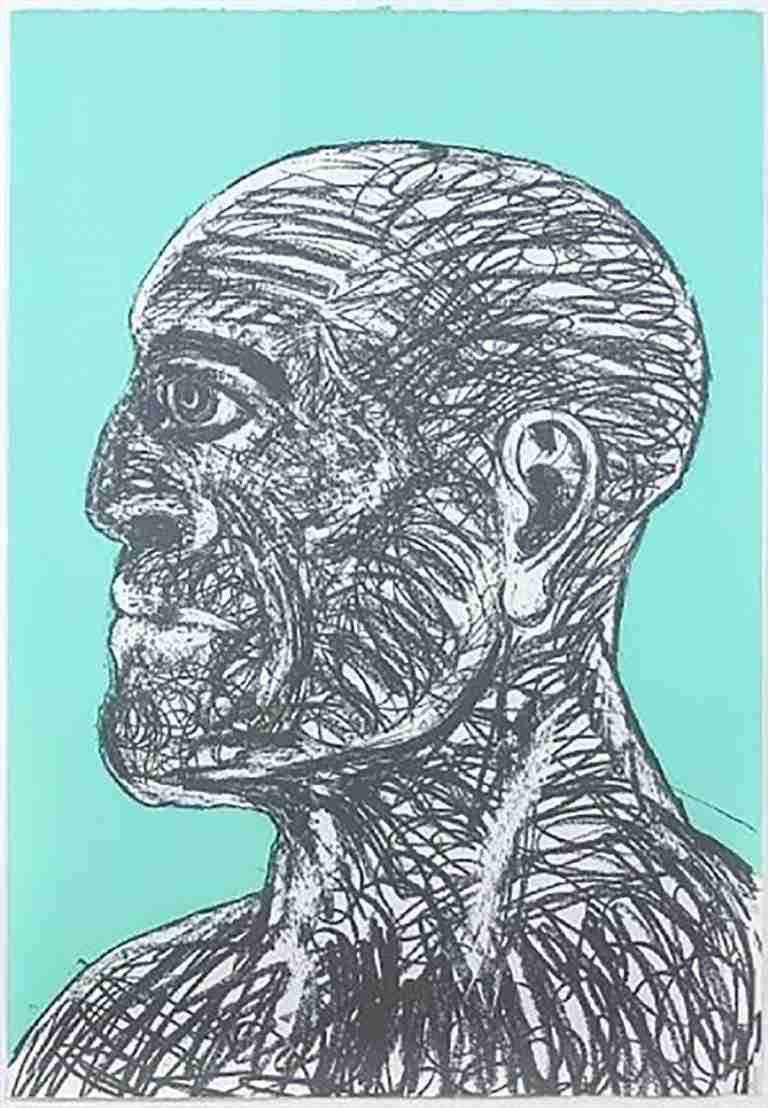

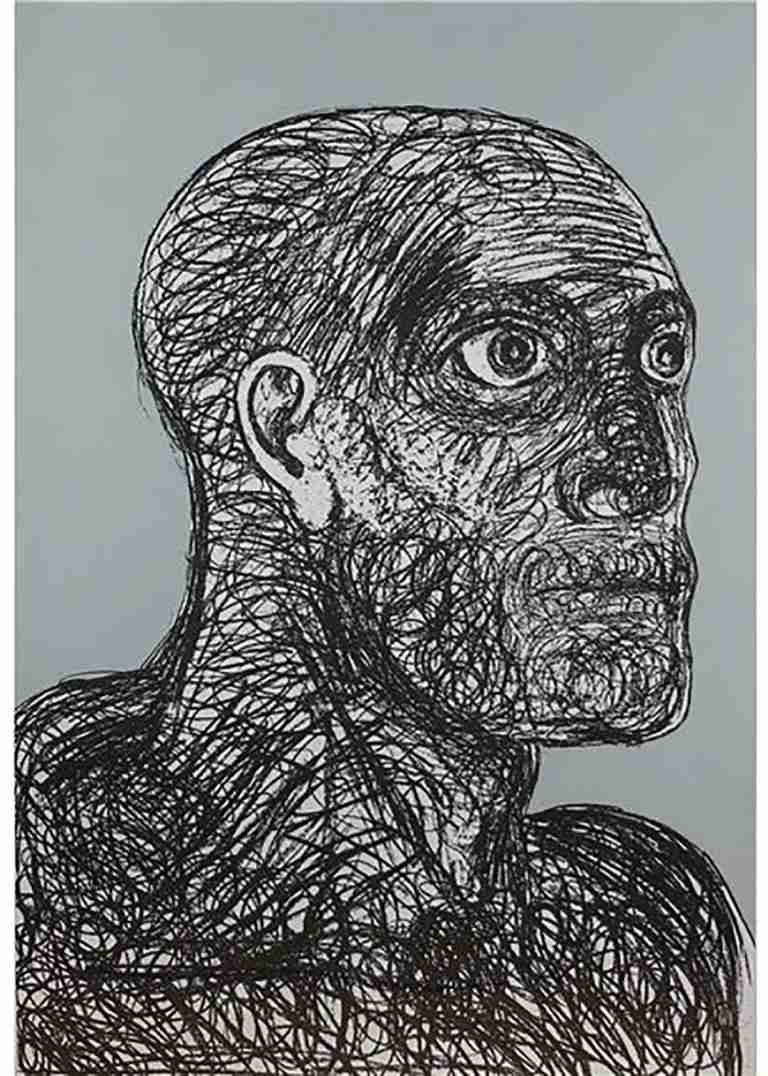

2021 Man is Animal (catalogue), Gerhard Marcks Haus, Bremen, Germany Introduction by Arie Hartog, ‘From Hero to Zero (and back again) About the heads of Elisabeth Frink’ by Feico Hoekstra, ‘In their Nature’ by Peter Murray,

‘A Very personal look at Antiquity: The Riace Warriors by Elisabeth Frink ‘ by Veronika Wiegartz

2023 A View from Within, (catalogue) Dorset Museum and Art Gallery, Dorchester. Introduction by Elizabeth Selby, ‘Elisabeth Frink: A View From Within’ by Annette Ratuszniak, ‘Remembering Frink’ by Lucy Johnston, ‘In Search of Humanity: The Early Career of Elisabeth Frink’ by Wilfrid Wright, ‘Elisabeth Frink at Dirset Museum & Art Gallery’ by Elizabeth Selby and Emma Talbot.

2024 A Celebration, (catalogue) Beaux Arts, London

Public purchases since 1993

1997 Dying King

1963 Torso

1958 Goggle Head

1968 Riace I (Walking Man)

1987 Tate Collection Public Collections

Great Britain Arts Council, London Atkinson Art Gallery, Southport Birmingham City Museums and Art Gallery Bolton Museum and Art Gallery British Museum, London Dorset County Museum, Dorchester East Haydock Branch Library, St. Helens Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge Ipswich Museums and Galleries Leicestershire Museums Middlesbrough Art Gallery Oldham Art Gallery Portsmouth City Museum and Art Gallery Royal Academy of Arts, London Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon, London Salford Art Gallery Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, Salisbury Scottish Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh Sheffield City Art Galleries Sutton Manor Arts Centre, Winchester Tate Gallery, London Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool Whitworth Gallery, University of Manchester

United States of America Carnegie Institute, Museum of Art, Pittsburgh Chrysler Museum, Provincetown Joseph Hirshhorn Collection, Washington Museum of Modern Art, New York

Australia Brisbane Art Gallery National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

South Africa South African National Gallery, Cape Town

Public Places Yorkshire Sculpture Park Royal Opera House, London Warwick University Grosvenor Square , London Outside WHSmith headquarters, Swindon, Wiltshire K & B Plaza, New Orleans, USA Dorchester Hospital, Dorset King’s College, Cambridge Exchange Square , Hong Kong Bristol Museum The Montague Shopping Centre, Worthing Royal College of Physicians, London Chatsworth House, Derbyshire Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge West façade, Anglican Cathedral, Liverpool