As a child, visiting relatives in Belmullet, County Mayo, I was told that Tír na nÓg – the Land of Youth where the mythic warrior poet, Oisín, lived for 300 hundred years – could be seen off the coast. Even then, I realised that if you stared out into the grey mists of the Atlantic for too long you would see all sorts of things. But these reported sightings did bring home the degree to which Irish mythology was alive in that community on the western seaboard. Geographical isolation, the survival of a robust oral culture, a strong sense of belonging and a close connection to the land and the sea, created a context in which mythic figures including Oisín, Connla and Étaín were still relevant.

Oisín plays a central role in Anthony Scott’s new exhibition at Beaux Arts and is depicted twice on horseback. In the story Oisín falls in love with Niamh of the Golden Hair, daughter of Manannán mac Lir, god of the sea. He follows her to Tír na nÓg where they live happily for a period. After three years, Oisín becomes homesick and wants to visit Ireland again. Niamh lends him her magical horse but warns him not to touch the ground. Arriving on the West Coast, Oisín soon realises that three centuries have passed. His family and friends are long gone and the Irish are a much diminished race. Scott depicts two key points in the story: the moment when Oisín turns back to help a group of men struggling to move a large stone, and his subsequent fatal fall from his horse. As soon as Oisín touches the ground, the spell of Tír na nÓg is broken and time catches up with him. In some versions of the story, St. Patrick converts Oisín before he dies thus signalling Christianity’s victory over the old Gaelic gods.

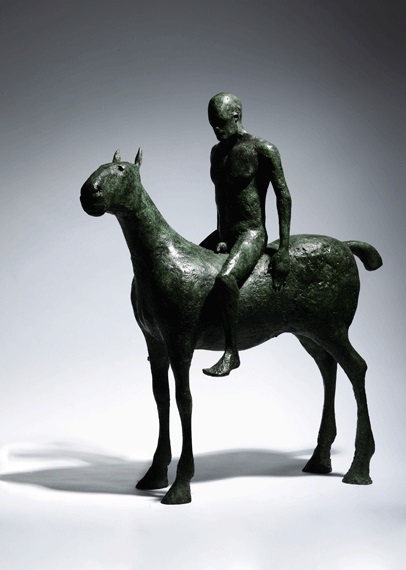

Scott portrays one of these gods in his image of Nuada on horseback. Nuada was the first King of the Tuatha dé Danann, a divine race thought to represent the deities of pre-Christian Ireland. He was forced to give up his position after losing an arm in battle because tradition demanded that the leader must be physically perfect. Nuada solves this problem by having a silver arm made. Thus, this tale could be seen as an allegory for the transformative power of art. Scott’s sculpture, which depicts Nuada rejoicing just as he is restored to his position, is reminiscent of Mario Marini’s equestrian sculptures including The Pilgrim (1939) and his iconic work The Angel of the City (1948) from the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. Scott has acknowledged the influence of this Italian sculptor, who reimagined the traditional equestrian portrait in a modernist language.

Another significant precursor is Elizabeth Frink whose sculptures of horses, animals and figures exhibit a kinship with Scott’s work. The key themes of Frink’s oeuvre have been described as ‘the nature of Man; the ‘‘horseness’’ of horses; and the divine in human form’.[i] These preoccupations are shared by Scott. Like his horses, Frink’s sturdy War Horse (1991) and the elegant Black Horse (1978) embody something essential about the nature of the animal and exhibit a deep appreciation and understanding of them.

An affinity with Frink’s figures, such as Dorset Martyr (1985/6), can also be discerned in Scott’s sculpture Connla. His first large scale figurative work, Connla is an imposing male nude who tenderly cradles a young dog. For Scott the work is about a father’s ultimately futile attempt to save his son. In order to try to protect his son from the goddess Danu, Connla asks the Druid Conaire to hide him. Connla means warrior hound, and in Scott’s version, Conaire turns the boy into a dog. Standing larger than life, Connla conveys a powerful sense of presence. Like the horses that Scott so successfully imbues with the impression of vitality, this figure seems more nature than art: less a sculpture cast from a mould than a living figure bewitched into bronze. Connla’s determined brow owes something to the artist’s own features and Scott’s recent experiences of becoming a father also resonate with the theme of this work.

Trained as a ceramist, Scott sculpted in clay before turning to bronze to accommodate larger and more durable work. The influence of his training may be discerned in both his methods and the careful attention he pays to the texture and patina of this work. Although, some of the larger sculptures including Connla were created in plaster before being cast, Scott often works in wax which, like clay, is soft and malleable. His efforts to achieve the correct patina can be laborious, but with the help of skilled craftspeople at Cast, his foundry in Dublin, Scott has created a rich repertoire of patinas which he selects depending on the atmosphere and feeling of the work. Thus Connla is rendered in a textured lichen green, the foal Étaín has a smooth coat in mottled hues of fawn and oatmeal and other works are finished in rich red browns or steel blue.

The figure of Étaín is sometimes known by the epithet Echraide (horse rider) suggesting links with horse deities and figures such as the Welsh Rhiannon. In the myth, Midir of the Tuatha Dé Danann falls in love with Étaín. When he marries her, his rejected first wife, Fúamnach, becomes jealous and casts a series of spells which eventually transform Étaín into a butterfly. In this bewitched form Étaín has many adventures before being reborn several centuries later. Scott has interpreted her at the moment of rebirth as ‘a foal finding her feet for the first time, that first lung full of air’.[ii] He goes on to explain that ‘It comes from experiencing a foal’s birth on my uncle’s farm when I was very young, it seemed to connect for me with the characters narrative arc’.[iii] Coincidently, étain is also the French word for tin or pewter and, in the past, it was tin that was mixed with copper to create bronze.

Growing up in a rural community, Scott was surrounded by the horses, dogs and bulls that feature in his work. He recalls walking to school across the fields and his appreciation for the animals he encountered on that commute, both wild and domestic, is expressed in his sculptures. There is something totemic about these animals. It is as if the mythical figures they are named after are reborn – like Étaín – through kinship with the animal. Scott’s fascination with Irish mythology was fostered by the discovery of Thomas Kinsella’s The Tain, his 1969 translation of the Irish Epic, Tain Bo Cuailng. Accompanied by Louis le Brocquy’s brush drawings which enrich the text rather than illustrating it, Kinsella’s translation of The Tain tells the stories of the Ulster Cycle which centre on the Cattle Raid of Cooley and the exploits of the hero Cúchulainn – the Hound of Ulster. Throughout The Tain the division between humans and animals is blurred, for instance The Morrigan, whom Scott has used as a subject in the past, is both supernatural woman and a crow whose foreboding presence brings death and destruction.

Clearly, Irish mythology is central to Scott’s work but, unlike many of his artistic predecessors, including George Russell (AE) and Harry Clarke, who imagined the mythic characters as ethereal and insubstantial, Scott’s sculptures are rooted and weighty. They convey a sense of presence – of occupying space – that makes them feel real, not only as portraits but also as objects occupying our world. This sense of physical substance and psychological presence, transforms Scott’s sculptures from inanimate mass to animated form. Connla, Oisín and Nuada become monuments to beings that once lived, rather than purely artistic imaginings of myth.

[i] Obituary, The Times, April, 1993 [ii] Anthony Scott, email to the author, 23/2/2015 [iii] Ibid