Anna Gillespie

1964 Born 1983-86 BA Hons Philosophy, Politics and Economic at Wadham College Oxford University 1986-87 Diploma International Relations, LSE 1996-98 MA Fine Arts, Cheltenham

Exhibitions

2019

Commission for Morecambe Bay Partnership at Half Moon Bay

Elected Academician at the Royal West of England Academy

Collaboration with Richard Chappell Dance, funded by Linbury Trust and Arts Council

CoLab Drawing Residency, Historic Collections and Owlpen Manor

The London Art Fair, Beaux Arts Bath

The Hepworth Wakfield Print show with Spike Island Print Studio

Shortlisted for Women Make Sculpture prize organized by the CoLab

2018

Beaux Arts Bath. Solo exhibition

Commission for Crest Nicholson at Bath Riverside

The Steel Rooms. Solo exhibition. Brigg, Grimsby

Two person show Christies Contemporary, Jersey

Collaborating with choreographer Richard Chappell. Preview at Royal Opera House

Grizedale Sculpture Park. Group RBS exhibition. Inspired by Nature

London Art Fair, Beaux Arts Bath

Member Spike Island Print Studio

2017

Installation ‘The Waiting’. Baltic Triangle, Liverpool

Society of Women Artists. Group show. London

Royal West of England Academy, Drawn group show

Beaux Arts Bath, London Art Fair

Residency. Drawing Projects UK

CCA Galleries International, Jersey. Four person show

2016

Acclimatize E-exhibition Moderna museet, Stockholm

The Pound Arts Centre, Corsham. Solo exhibition

RWA, Autumn Exhibition

Beaux Arts Bath. Solo exhibition

Open Studio Show, Bristol

Lacock Abbey, group show

2015 Beaux Arts London, Solo Exhibition Beaux Arts London, Summer Exhibition Glastonbury Festival, Greenfields gateway commission RHS Chelsea Flower Show with Chris Beardshaw Frensham Heights School Commission London Art Fair, Beaux Arts Bath 2014 National Trust Headquarters, Heelis, Swindon Glastonbury Festival, Greenfields gateway commission Art in Action, Oxford, July Alderney Performing Arts Festival, June, July, August Beaux Art Bath, Solo Exhibition London Art Fair, Solo Stand , Beaux Arts Bath January RWA, Autumn Exhibition 2013 Beaux Arts London, Tree Exhibition with Sarah Gillespie, Marilène Oliver, Stephanie Carlton Smith London Art Fair, Beaux Arts Bath Gloucester Cathedral, Open West group Show Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition 160 Autumn Exhibition, Royal West of England Academy London Art Fair, Beaux Arts Bath RHS Chelsea Flower Show, Chris Beardshaw Gold Winning Garden Glastonbury Festival, Greenfields gateway commission Beaux Arts London, Summer Show 20/21 Royal College of Art Fair with Beaux Arts Bath STRARTA 2013 Saatchi Gallery with Beaux Arts Bath 2012 London Art Fair, Beaux Arts Bath Two Person Show, Beaux Arts Bath Beaux Arts London, Summer Show RWA, Autumn Exhibition Abbey Walk Gallery, Grimsby, Group Show 20/21 and Art London Art Fairs with Beaux Arts Bath Derwent Wye Fine Arts-Group Show 2011 London Art Fair, Beaux Arts Bath Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition Burghley House, Sculpture Garden The Big Draw Self-Portrait Drawing Show, Chapel Row Gallery, Bath Work also shown at Byard Art, Cambridge and Artzu Gallery, Manchester 2010 London Art Fair, Waterhouse & Dodd Three person show with Peter Randall-Page and Sarah Gillespie. Waterhouse & Dodd, London Cambridge -Solo Show. Byard Art, Cambridge SEEDS Film Festival. Minneapolis, USA Art London, Beaux Arts Bath London. Victor Felix Gallery, Three person show 2009 London. Art London Fair. Byard Art Manchester. Artzu Gallery. Solo Bristol Contemporary Open. Group Show Bristol. View Gallery. Opening Group Show 2008 London Art Fair with Victor Felix Gallery London. “The Figure” at Sarah Myerscough Fine Art London. “Coda” with Chuck Elliott at The Gallery in Cork Street Plymouth University. “Artspaces”. Group Show 2007 Bristol. Royal West of England Academy. Open Sculpture London Art Fair with Victor Felix Gallery London, New York, Amsterdam, Affordable Art Fair with Victor Felix Gallery Chapel Row Gallery, Bath Solo Show Beaux Arts Bath, Summer Show Cambridge. “Breath of Fresh Air” and Summer Show, Byard Art Oxfordshire. Art in Action Corsham. Pound Arts Centre, Solo Show 2006 Art Miami Art Fair with Osborne Samuel Gallery Palm Beach Art Fair with Osborne Samuel Gallery London, Affordable Art Fair, Battersea ArtzuGallery London, Osborne Samuel, Summer Show Manchester, Artzu Gallery, Group Show Oxfordhsire, Art in Action 2005 Bristol. New Gallery at the RWA. Solo Plymouth. Peninsula Art Centre. Four person show London. Osborne Samuel. Three person show Frome, Somerset. Black Swan Arts. Buckfastleigh, Devon. Rill Centre London. Osborne Samuel Gallery. Summer Show Bath. BANA group exhibition London. The Artist and Radio 4. South Bank Gallery Manchester. Artzu Gallery. Big Shots 2004 Bristol. R.W.A. ‘Encore’ group show London. Candid Arts Trust. Network A.D. group show Bristol. Centrespace group show Bristol. Tobacco Factory. Black Cube group Bristol. South Bristol Art Trail Bath. Fringe Festival. Installation in Bath Abbey Yorkshire. Hebdon Bridge Sculpture Trail London. ‘Art London’ with the Berkeley Square Gallery Athens. ARTiade 2004. ‘Olympics of Visual Arts’ Gloucestershire. Prema Arts Centre. Solo London. Spectrum Fine Arts Bristol. RWA. Autumn Exhibition Bath. Hotbath Gallery. Pause: capturing the sublime Exeter. Home is Where the Hurt Is Plymouth. New Street Gallery. Christmas Show Ashburton. Gallery No 8. Christmas Show Somerset Museum Services art collection 2003 Bristol. Centrespace Gallery. Solo Dorset. Sherborne House Arts Centre. Two person show R.W.A. Open Bristol. Botany Studios. Open studio show. Bristol Black Cube group. UV light exhibition Lichfield District Council. ‘Inspire’ 100 people collaboration 2001 Salisbury. Site-specific stone commission for Lord Chichester Birth of second son 2000 Italy. Chiostro della Collegiata. Group show. Casole d’Elsa, Siena 1999 Birth of first son Bristol. Work shown at The 3-D Gallery Totnes. Ariel Centre. Work shown alongside solo exhibition of paintings by Sarah Gillespie 1998 Work shown at the Gardens of Gaia Sculpture Park, Kent. 1998-1999 Work shown at the Michael Wright Gallery, Bristol 1997 Italy. Scholarship and teaching assistant at the Centro d’Arte Verrocchio Ireland. Work shown at the Yello Gallery, Kinsale. 1997-1998 Gloucestershire. Work shown at the Anderson Gallery. 1997-1998 1996-98 MA in Fine and Media Arts. Cheltenham 1996 Italy. Studio assistant at Centro d’Arte Verrocchio Bristol. The Happening Gallery. Solo London. Work shown at The Cadogan Gallery London. Work shown at The McHardy Sculpture Gallery Worcestershire. Work shown at the Ombersely Gallery Bristol. Group show by ‘Artery’ at the Leadworks Edinburgh. C Venue 19. Fringe Festival five women show 1995 Bristol. The Happening Gallery. Solo Bristol. The Happening Gallery. ‘Cruciform’ group show London. Wembley Exhibition Centre. Natural Stone Show City of Bristol Museum & Art Gallery. ‘Broad’s Boards’ Edinburgh. C Venue 19, Fringe Festival group show R.W.A. Open. Italy. Studio assistant to Nigel Konstam at the Centro d’Arte Verrocchio 1993-95 R.W.A. Printmaking Open Bath Society of Artists. Open R.W.A. Open

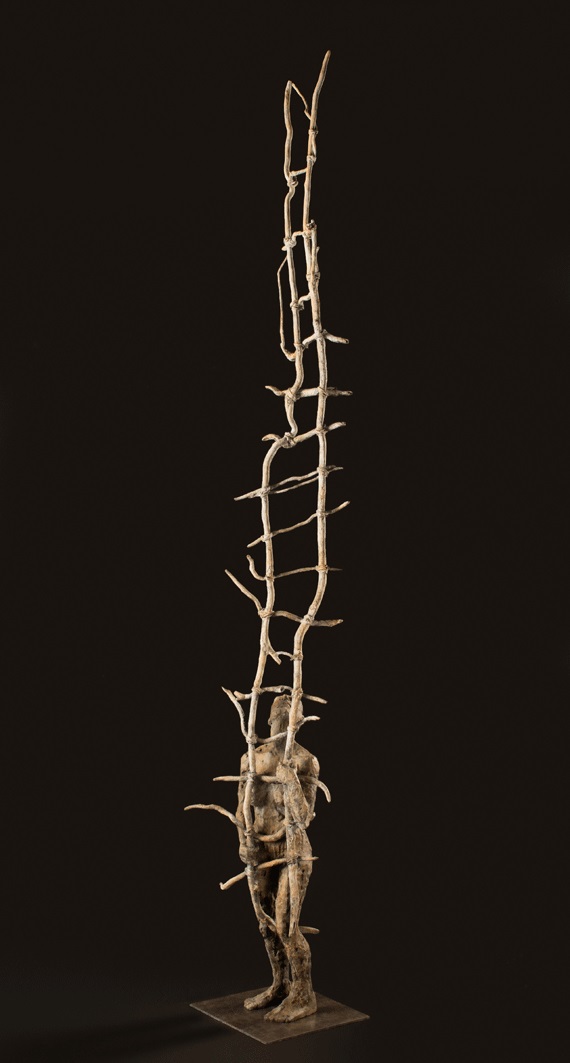

In his famous, and seminal, aesthetic treatise on Laocoon, the great 18th Century philosopher and poet G.E. Lessing, found himself asking the fundamental question, one that seems to echo with undiminished resonance, right down into the 21st Century ‘What is sculpture?’ The answer to that question was the assertion that sculpture is an art concerned with the deployment of bodies in space, its defining spatial character separating it off from other art forms, such as poetry, whose essential medium is time. Sculpture is, in short, static, the separate parts that make it into a visual object being taken in by the viewer simultaneously, all at once. It is an idea that has had enormous influence in the early 20th Century, with influential Modernist critics focussing almost exclusively on the spatial character of the medium to the exclusion of virtually anything else. It was also an idea that, predictably enough, had to unravel somewhat, as Lessing himself anticipated when he added the cautionary words “all bodies, however, exist not only in space but also in time.” They were words which began echoing increasingly in my head as I looked at Anna Gillespie’s most recent body of work, sculptures which, in their astonishing, latent energies seem, as Lessing well understood, to speak of the movements and actions that both precede and follow their present state.

The artist who, perhaps more than any other, introduced the human figure as an existential (rather than formal) being back into 20th Century sculpture was, of course, Giacometti. Though he is an influence that has never been cited in Gillespie’s work, the element of surprise that is such an integral element in his figures as they emerge into existence, the space that radiates both outwards and inwards from them and the sense of a figure over time implicit in them, would all seem to be key elements in her work over the last 10 years or more. The artistic impulse is not so much a stylistic thing but more a question of the artist’s almost unconscious or instinctual response to the particular times in which he/she lives, the Zeitgeist if you like. For Giacometti that was made up, in equal measures, of the post-war revelations of the Holocaust and the annihilating possibilities of the atomic bomb; for Anna it has been first, the trauma of watching 9/11 and the American’s entry into Afghanistan unfold – “I sit in front of TV watching it and realise- as I see people of all races in New York looking up at the skyscrapers – that it is possible to make work about what it is to be human without that work being autobiographical. A kind of epiphany sending me back to figuration. Over the coming months there were endless images in the news of people kneeling, hands behind backs and with hoods over their heads”; and then again, in the winter of 2007, “ as the reality of climate change viscerally hit me” finding it “increasingly difficult to work when the world was in crisis – it seemed the wrong thing to do. This was not an intellectual crisis but a deeply felt one.”

Gillespie’s profound artistic reaction to these two crises has been, in many ways, a measure of her strength as a sculptor, with 9/11 returning her to the figure but in a way that, unlike Anthony Gormley, was not primarily autobiographical but a realisation, as she puts, “that the figure could be a crucible for different concerns – environmentalism, emotions, the human condition.” Meanwhile her subsequent personal crisis concerning the environment resulted in her signing up for a course called ‘Art in Place’ at the Schumacher College in Devon. An inspiring tutor there, Peter Black and two significant visiting teachers, Peter Randall-Page and Anthony Gormley, all helped provide a vital focus and make her really believe that her sculpture could be “of service at this time of crisis for the planet – my contribution to part of the solution.” While Gormley’s example made her realise she really didn’t want her own body to form the focus of her sculpture, as indeed it never has done, Randall-Page’s has been very much more positive, inspiring her with the idea that you could make works about nature that were contemporary in character and went beyond merely mimicking its forms. This has led first to works like For the Love of Oak, L’Enfant, Trust and Dappled Sleep in which acorn cups (and other tree-based materials, as in Last Leaves), all personally gathered, often from individual trees, and then applied to sculpture’s surface, have provided the rich and complex surface texture for pieces finally cast in bronze. It also led to another whole strain of works like But for the Grace of God, The Fallen, Harbourside and Old Giant, often more political in character, in which small, solidly-cast figures are incorporated into found metal and wood objects – old oil drum lids, sections of girders and tree stumps for example.

She talks about how both these groups of works, now spanning some eight years of practice, can “breathe the beauty of nature into built spaces such as galleries” but they represent perhaps also something rather more than that perhaps, both for her and for us, as viewers. The time spent under the trees, for example, gathering the acorns becomes, as she puts it so eloquently, “a deep thought, a meditation and a levelling thought too that, while each acorn or cup is the same, it is also different and that, outside this ‘norm,’ there are also a few which are formed with a radical difference and yet are still recognisably the same as others – just like us humans.” It is, as she herself recognises, an exercise in profound humility, one that has, perhaps, been born out of a much wider, more recent and quite profound philosophical shift in our attitudes towards Nature (not shared so widely yet within the physical sciences) in which we no longer see ourselves as, somehow, ‘outside’ Nature but as very much within it, one creature existing among myriad others. It maybe the very simplest of thoughts but one that needs to come as felt experience to take on its full power, the very lack of which within our culture preventing us from understanding that our destruction of Nature is in fact the destruction of ourselves. Her gift, and the innate power of these sculptures to affect us, comes, I suggest, from just this sense of time passing and the due process that lies within their making – these massive ‘acorn’ figures radiate powerful sensations of thought and feeling, which pulse in and out of them, touching and catching us almost unaware, and thus profoundly.

There is, too, a significant new variation on these themes emerging in the most recent of her pieces in this show, many of them involving two figures or more, most notably Rescue Me, Let it Rain, Heaven’s Gate, Freefall (originally intended as three grouped figures) and They Paved Paradise. In all of them the subject matter is very much a move away from the kind of solitude felt in the face of nature of the ‘acorn’ pieces and towards a much more shared experience of Nature’s forces. This is particularly apparent in Let it Rain and Heaven’s Gate where it is the nature of physical love and an experience of awe at being subsumed in nature that would seem to be the overriding sensation. Rescue Me, on the other hand, is perhaps about something else again; its origins lie in a piece made some years ago, entitled The Ghost of Summer, a small winged figure form that had come to her in a dream, the wings being made out of leaves that had fallen in her garden that autumn and then painted with wax and moulded directly. It immediately (within a week) prompted two more similar winged figures, one of which was also entitled Rescue Me. This particular work touched many people powerfully at the time and encouraged Anna to see if the figure could be made, half life-size and without wings, and for it still to hold this same degree of compassion. The answer is unquestionably yes, not least in the limp arm of the second, carried, man, its loss of power and sense of vulnerability echoing those similar gestures to be found in several Michelangelo paintings and sculptures, his Pieta above all. There are, for her too, some intensely personal echoes to be found here too – the unintentional recreation of her father’s face – “underneath my father’s self-made, bolshy, talented, strong exterior was someone who needed rescuing.”

The other significant point to be made about these latest pieces is the utterly different process she is using to make the maquettes for them, namely a wax technique that enables her to adjust, alter and shape the figure right up to the moment it is cast, something that was largely impossible with the ‘acorn’ method, for example, or even in plaster. It also, more significantly still, seems to impart to the surface a flickering, almost ephemeral, quality that hints at a much wider range still of emotional subtlety. It is, above all though, part of Anna Gillespie’s ongoing fascination with the nature of the sculptural process, of matter as a revelator of unconscious emotion and thought. The great, late 20th French philosopher Gilles Deleuze had some profound things to say on this relationship between matter and intensity in modern art: for him artistic intensity no longer lay in the relation between matter and form but rather in that between material and force. The artist takes a given, energetic material with all its intensive traits and particular qualities and then synthesises them in a way that it can harness these intensities. Paul Klee called it “the force of the cosmos”. Gillespie, with her rich interweaving of materials, emotions and ideas, full of revisitings and circularities, may just have begun to find a way to tap into this for herself, making her a sculptor to take notice of not just now but in time to come also.

Nicholas Usherwood

It’s impossible to remember exactly when I saw my first Anna Gillespie sculpture, but I know it was in the Beaux Arts Gallery Bath, and was a figure encased in acorn cups. There was something so profound about that marriage of humanity and nature, of ‘flesh’ transmuted into another organic substance, that I was deeply moved. Since then I dream of living among her creations. It is as if her figures have a permanent home in my imagination, reaching out their arms in supplication, pleading for a deeper understanding of the relationship between humankind and the world we inhabit.

It was tempting to write ‘our world’ – yet Anna Gillespie would surely reject that possessive pronoun. Her figures often seem shackled by their human form, weighed down by humility: the awareness that they are but small parts of a much greater whole. Their message is that we are merely bit players in a colossal natural drama which gives the starring roles to trees (their wood, twigs, seeds and fallen leaves) and to rusty artefacts dug from the earth, and to stone and wind. Those works which incorporate tiny bronze humans within (or on top of) large ‘found’ objects encapsulate this idea perfectly. We are so small but the world is large – and always demands our attention.

That is not to say that the human figure is not worthy of attention too. But often it appears to be sad or yearning or rapt, as if in contemplation of the circular nature of life and death. So the beech tree unfurls leaves which will later fall crisply to nourish the earth, as the four‐valved husks are raided by squirrels for nuts and shaken to the ground to rot – or perhaps to be gathered by Anna Gillespie. It goes on and on, this cycle of losing and giving. The crouching figure, ‘Gathering Time’ (which is the work I possess) is scooping up fallen husks, holding them to her face as if to worship a beauty which is doomed and yet (glorious paradox) always being re‐made. For me, as a writer, the poetic ambivalence of that title – and so many others – is a reminder of the exquisite intelligence of this artist whose educational background crosses many disciplines. The sculpture shows the time of gathering but also a gathering up of transience, as if by embracing time you might stop its perpetual motion. And in bronze it is caught forever.

In such work the distinction between the human and the natural world is blurred, reminding me of Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses,’ in which people are transformed into trees, birds, and flowers. In all the tales transformation is an act of mercy – so the self‐obsessed, lovelorn youth Narcissus becomes a flower instead of suffering death, and the devoted old couple Baucis and Philemon are changed into trees at the same time. There is real compassion in Gillespie’s work too, and she understands that miraculous and merciful process of becoming. For in those sculptures which do not make use of the twigs and seeds which became a characteristic so beloved of her admirers, there is still a struggle to break free of what was and become something else. So a white figure is imprisoned within a stone wall, and people wrapped in duct or masking tape are infused with extraordinary energy and given the gift of flight.

This is the work of an artist at the height of her powers, who is involved in an endless process of change herself – a serious, passionate quest for synthesis.

Bel Mooney, 2013

Anna Gillespie at the Royal Chelsea Flower Show with Designer Chris Beardshaw 19 May – 23 May 2015 ‘Within the design Chris has considered the mechanism of what makes a city healthy and, by definition, what creates a healthy community. The formal geometry of paths, hedges and walls symbolise the physical infrastructure of a community, while vibrant plants denote the social elements within as they are diverse in origin, colour and character but work together to form a successful community..’

(Text courtesy of www.rhs.org.uk)

4th September – 5th October

1st July – 26th August